By Sara DeMartino

Institute for Learning

Authors use language in lots of different ways in their writing, but for analysis questions you really want to focus instruction on the gems, on the elements of craft that an author does really well and merits study. In this article we’ll describe what we mean when we say analysis tasks and provide an example of what an analysis task might look like for a complex text.

What do we mean by analysis task?

When we talk about analysis tasks, we are talking about tasks that ask students to look at how the author works as a writer to get their ideas on the page and to communicate those ideas to the reader. This kind of text-based work should focus on the author’s craft—how grammar and language are used to create an effect, develop an idea, or make an argument. This doesn’t mean that students should be invited to examine every use of punctuation or figurative language that an author uses, but that when warranted, students are asked to dig-in to the aspects of an author’s writing that students can genuinely learn from.

Key Features of an Analysis Task

-

- Invite careful study of interesting, important, and significant aspects of an author’s style that have broad transferability to other texts and students’ own writing.

- Focus readers’ attention on how an author’s style shapes meaning.

- Invite students to try out the techniques in their own writing.

- Invite extended responses that are articulated in oral and written summaries, explanations, and arguments.

Analysis tasks should use student-centered routines to support students in responding to open-ended questions that take students deeply into discussions of and writings about an author’s methods or craft in and across texts. These questions often (but not always) can sustain multiple, varied responses using textual evidence. Analysis work often leads to invitations for students to write like the author—to imitate the author’s style, sentences, grammatical structures, etc. Write-like work deepens students’ understanding of elements of craft, asking students to use texts as mentors as they try out an author’s methods for themselves, working to add to their own repertoire of writing tools.

What does an analysis task look and sound like?

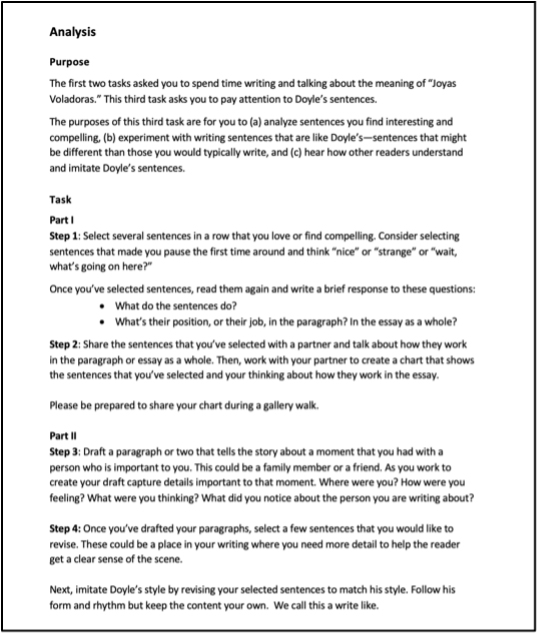

“Joyas Voladores” (Doyle, 2012) is a complex text in which Brian Doyle writes about the paradox of the heart. He argues that the heart is what unites us but says we can never really be united; it’s what gives us all life, but also destroys us. Doyle uses several craft elements in this essay as he develops his point—students could be asked to study his use of figurative language or how he specifically uses commas. There are a lot of craft elements in this essay, but remember, we are looking for the gems. Rather than try to capture everything that Doyle does as a writer in this text, we chose to focus in on sentence structure. While that seems like a broad category, Doyle’s use of sentences creates a sense of rhythm that mirrors the pace of the heart that Doyle is describing. Because the heart is central to Doyle’s essay, inviting students to study Doyle’s sentences and focusing on the rhythm he creates (and knowing how that rhythm ties back to the heart) keeps students’ work focused and lends itself to creating a coherent arc of work that enhances what students understand about Doyle’s overall message.

In this sample task, students are first asked to identify sentences they find compelling, sentences that stand out to them in some way. With an essay such as Doyle’s, just about any grouping of sentences that students select will give them something to write about and tie back to the discussion of the heart and Doyle’s use of rhythm. Students are then asked to describe what they noticed about these sentences. The act of describing what students understand about the sentences helps students to surface their own knowledge about writing. It’s okay if students don’t have the academic language to describe what the sentences do. If a student says that Doyle writes fast in the lines she selected, for example, the teacher as the facilitator, or better yet, other students, can help that student name, for example, that Doyle uses short, simple sentences and lots of commas to create speed and a staccato feeling when writing about the hummingbird.

Once they have had an opportunity to examine Doyle’s sentences and discuss how they function in the essay, students have an opportunity to write like the author, trying out the methods they identified in Doyle’s essay and reflecting on the process. In the example task, students are asked to draft a paragraph about an important moment they have had with a person important to them and then revise a few sentences where it might make sense to write like Doyle. However, students who have been keeping a portfolio of their writing or are concurrently working on an essay while reading Doyle’s essay might be asked to make the revision to a work in progress and reflect on what the revisions do (or do not do) to help the reader understand the main point of the student’s essay.

A note about sequencing of tasks

This article, which focuses on text analysis, is a companion for our October comprehension article. We wrote about comprehension first because comprehension should be the first task undertaken with students on any text, especially if we want students to go beyond superficial understandings of authors’ ideas and think about how authors work as writers to develop their works. We also want to scaffold the cognitive load we put on students as they engage with increasingly complex text.

Let’s imagine that during their first read of “Joyas Voladores” students are asked to respond to the following question:

How does Doyle’s tone in “Joyas Voladores” help you understand his purpose for writing the essay?

We often see a variation of this question pop-up in classroom instruction when teachers are working to address the standards that they know will be tested come state testing season. The issue with this question arises when students are asked to respond to this question after their first reading of the text. Let’s take a look at the process that students have to engage in to respond to this one question (with a really complex text):

The question requires students to make sense of Doyle’s tone and purpose all while grappling with the content of his essay and making sense of exactly what Doyle is saying. This becomes especially problematic when students haven’t yet had the opportunity to state what they think Doyle is saying (his big ideas) in this essay, hear from peers about their thinking, and then work as a whole class to make sense of those big ideas first. Without that comprehension work, a question such as the one shown above may generate student responses that range from students trying to make sense of the big ideas (which we should see as students waving at us, telling us they need comprehension first!) to students attempting to answer the parts of the question with an incomplete understanding of the essay, to students who are “getting it” but taking a lot of time to do so (because it was a really hard task to ask of students on a first read). If students first have the opportunity to state what they understand Doyle to be saying, two things can happen. First, the teacher can assess where students are in their understanding of the text and make adaptations to the follow-up work to either deepen student understanding or move on to a task such as the one shown. Second, students can engage in the task shown above, coming back to the text with an understanding of the ideas, so that they can focus their mental energy on understanding purpose and tone.

In our next article, Tequila Butler will introduce you to two teachers from the Dallas Independent School District who have been working to develop analysis tasks. They will speak of the benefits of inviting students into the text through comprehension work first and how the comprehension work has led to more thoughtful and thorough responses to the analysis work.