How did you get interested in studying brain development in young children?

I got interested in this area after reading a series of papers that came out of a research unit at the National Institute of Mental Health that described the basics of how the brain grows and develops from childhood into adolescence into young adulthood. After learning about basic brain development, I started working with families that lived in very stressful conditions. For example, I worked with kids who had lived in Russian and Romanian orphanages after Ceausescu was deposed and the Soviet Union fell. Even though these kids had experienced pretty aberrant and abhorrent conditions, there was a lot of variability in the challenges they were having. For example, I met some kids who had lived in an institution for seven years, and they were fine, and you wouldn’t know that they had suffered that kind of intense trauma. Then, I worked with kids who had been in an institution for shorter periods of time, and they had a lot of challenges. Understanding why some kids were able to move through things and others have lifelong scars motivated me to understand how brains may change in response to stress and how these changes can impact the trajectory of a child’s life.

What are some of the main “takeaways” from your research looking at how the brain changes as a result of early life stress and trauma?

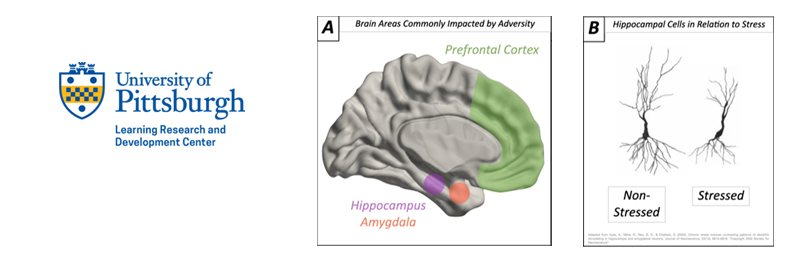

The biggest takeaways are first, that there are a lot of changes in brain circuitry involved with executive functioning. These are the control-based processes that help us think about thinking, plan for the future, inhibit distraction, and regulate behavior in the face of important or emotionally salient events. My colleagues and I started to see lots of changes in portions of the brain involved with those processes, namely in the prefrontal cortex. Basically, this front third of the brain is often smaller and has smaller rates of growth in those who have experienced trauma. There is less physical tissue there and often lower levels of activity.

The other kind of big set of changes happens in some brain regions involved with learning and emotion: the amygdala and the hippocampus. The amygdala is central to processing vigilance— telling us what to pay attention to in our environment. The hippocampus is central to learning about relationships—relationships within our environment and in different contexts. Differing kinds of early experiences can change the developmental trajectories of these parts of the brain. Particularly, we can see smaller regions over time, we think, because that region might be just working so hard it actually “burns itself out.”

With the hippocampus, this region also tends to be a little bit smaller. So again, you have tissue loss and often lower levels of activity. We think this relates to challenges with remembering information and not updating knowledge used in different environmental contexts (or settings). This could lead to perhaps overgeneralizing a learning or behavioral strategy too much.

Can you say more about what you mean by less material or tissue in the different brain regions?

Yeah, so for the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex, we see smaller amounts of tissue. We don’t have a great idea, though, if this is because there are less cells in these areas or if it is because the cells are smaller and less complex. Based on studies of non-human animals, we also know that there can be changes to the brain’s neurons. These are the cells in the brain that send and receive chemical and electrical signals and allow you to think, move, and feel. Neurons have these branchy bits called dendrites, which can retract with stress. In other words, if a rat has been exposed to a good deal of stress, their dendrites actually have less fibers—almost like a bush that has been trimmed.

Why do you think incredible stress causes these changes?

I think there are a couple of different possibilities, and my research lab is trying to arbitrate between them. So first, stress, very extreme levels of challenging things, activates the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis which increases cortisol. Cortisol in consistently high dosages causes brain cells to shrink and eventually in high enough doses to die. You have this chronic HPA stress system activation, and over time, that can alter the brain significantly.

The other thing is that the brain is built by experience. Different kinds of experience will cause things to strengthen or weaken like a muscle, so you can see enrichment and deprivation effects depending on the resources you have access to in your environment.

Finally, there is consistent reciprocity between the brain and behavior. An experience can exert an impact on the brain itself, often through a physiological cortisol-based means. But brain changes can lead to psychosocial challenges that also then affect the brain. For example, if you’re physically abused, that can cause an increase in cortisol. But, in the case of physical abuse, you have a lot of attachment disturbances, and so this might influence how you’re interfacing with your caregiver; so that’s going to cascade back to the brain where the specific adversity causes additional brain changes.

How do these early childhood brain changes influence outcomes for adolescents?

I think it’s very important to think about the lived experiences of people and the phenomenology of adversity, because any experience might be quite different and might exert quite different effects depending on what’s happening in an environment. We’re still unpacking this.

For example, if you experience physical or sexual abuse in your home, this is going to cause you to be pretty vigilant and keyed up to threats in that environment. You’re going to really watch yourself and make sure that after this really difficult thing happened, you are safe. This makes a lot of sense in the environment where the abuse happened. A lot of times, though, that kind of “teed-up-ness” comes out in other kinds of spaces that kids spend time in.

Many kids who have been physically abused have what’s called a “hostile attribution bias.” They believe that neutral things are more hostile. For example, a teacher might say something with benign intentions, but the kid actually sees hostility in what the teacher said, and this can lead the kid to be reactive, aggressive, or respond in a way that is unexpected or different. But it actually makes good sense when you think about the full life of a child. If they live in dangerous environments, it’s adaptive for them to be keyed up to any discrete displays of aggression or potential threat in those places. However, it may not be good to be as keyed up at school because a kid might really misread innocuous things that happen. They might think their teacher is out to get them or somebody who bumped into them at the water fountain did it on purpose, and that’s not necessarily true. In a way, we’re asking kids to “emotionally code switch” – to change between one belief and set of approaches in the world and then completely change to another. This can be hard for some kids, especially if a caregiver or school practitioners are not cued into what’s happening with the kid or doesn’t have training in trauma-related pedagogy.

Are there ways to compensate for the changes that happen in the brain as a result of early life stress? Are negative changes reversible?

First, when we talk about stress and adversity, it’s important to also think about resilience. For every kid who has had a really difficult experience and some challenges as a result, there are lots of other kids who don’t have those challenges. Even in really extreme cases where you see incredible amounts of stress and a two- to three-fold rise in behavior problems or depression, that still means that 30 percent of kids who faced these same stressors didn’t have these kinds of challenges.

One of the biggest sources of resiliency that I think is relevant for your audience are supportive adults outside the home. That’s one of the most well-replicated resilience findings. Having a supportive human and adult outside of your house is something that is massively buffering against the effects of stress, because I think you see a different vantage point in the world working in a different way.

Second, I do think that some of the negative effects of stress on the brain can be alterable. In fact, this is the predicate of therapy in adults. We often reverse some negative information patterns that we have if we’re depressed or anxious. Sometimes, it’s compensation, but a lot of times it’s reversal. We’re able to stop these patterns. In fact, researchers have studied people going through (talk) therapy, and you see changes in the brain as a result.

The other thing connected to reversal, or changing and disrupting some negative patterns, is compensation. One thing that we have to be careful about though is that some brain changes or patterns likely arose out of usefulness. I mentioned earlier that a kid may be hyper-vigilant to things in their environment for good reasons, though that vigilancy could cause trouble in a school setting. However, you don’t want to turn that vigilancy off. For instance, if you live in a rough neighborhood, this vigilancy might be helpful and adaptive, saving you from some harm or violence. Put another way—it might be good to look tough and “puff out your chest” so that you don’t get jumped going home. If someone just turned that behavior off or reversed this response, you might create other challenges for kids.

I think instead, we can maybe think about compensatory experiences that could alleviate or allow for some of the consequences of adversity to be lessened, or at least to be felt less by youth. If we were able to get kids to understand safe contexts and spaces where they’re okay and then say, “I know what it is like in this neighborhood. I know what it’s like on the walk home. And I get that. But hopefully, you can turn a little bit of that off or at least turn it down a little bit when you’re in school.” This is the emotional code-switching idea I talked about earlier. Creating safe, warm, and supportive spaces for kids could be a form of contextual learning. Kids could come to understand that the world may not be a warm and fuzzy place, but they can still feel warm and comfortable in their school. Schools themselves could be an intervention.